Know your Crafts

Kutch's craft industry is composed of over twenty one craft livelihoods. Craft is a living creative industry made from the hands of skilled artisans and generations-old tradition.

The rich and diverse creative traditions of Kutch live at the intersection of cultures and communities. Kutchi motifs can be traced to the ancient Harappan civilization, yet craft is developing and growing with the innovative and entrepreneurial drive of spirited artists.

The arid climate has pushed communities here to evolve an ingenious balance of meeting their needs by converting resources into products for daily living. Many textile crafts and hard materials crafts give this land color and identity. Craft is inextricable from the numerous communities, connected by trade, agriculture and pastoralism in Kutch.

Bandhani

Ancient Ties

Bandhani, derived from the Sanskrit word Bandha, which means to tie, is a traditional Indian tie and dye art, a resist dyeing technique, that uses closed threads for tying. Dating back to the 12th century, this art came to Kachchh when members of the Khatri community migrated from Sindh, and has since been culturally important to Kachchhi communities.

The Technique

The technique of tightly winding a thread around a section of cloth, dyeing it, and then removing the thread to reveal a circular resist motif has remained the same since Bandhani was first practiced.

Kala Organic Cotton

Rediscovering Local Cotton

The 'Kala' in Kala cotton, which means 'black' in many Indian languages, actually refers to the empty boll after extraction of the cotton fibre. Indigenous to Kachchh, this desi cotton crop is completely rain-fed and grown organically. The crop's resilience and resurgence to withstand harsh weather conditions, helps it form a coarse, stretchable fiber that makes it an all-time favourite fabric to be used in denims and other wearables. Once a significant part of India's cotton started getting exported to Britain, its use slowly and steadily disappeared. Today, after years of experimentation and perfecting both spinning and weaving techniques, Khamir is helping Kala Cotton create a new identity for itself in the market. Since 2010, as part of its Kala Cotton initiative, Khamir has been producing sustainable, modern-day handcrafted goods and encouraging sustainable cotton textile production in harmony with Kachchh's local ecology.

Mashru

A Fabric That Weaves Communities Together

Mashru means ‘permitted’ in Arabic, while it translates to ‘Misru’ in Sanskrit, which means ‘mixed’, since the fabric is a mix of silk and cotton. The earlier days saw restrictions in wearing silk since it comes from the slaying of cocoon and silkworm. That’s how and why Mashru came into the making: a medley of plush silk on the outside and soothing cotton on the inside. The Khatri community is believed to be the original proponents of this craft in Kachchh. The cotton to make this fabric was supplied by the Ahirs (farmers), while the Rabari and Ahir women would then add to the fabric charm with their embroidery and mirror work skills. Later as the demand of the craft increased in local and overseas market, the Khatris are said to have taught the craft to the Maheshwari weavers of Mandvi.

The Technique

A royal craft known for its intricate weaves and an impressive allure, Mashru is woven with a 7 to 12 paddle loom which requires harmony between the movement of hands and legs. The number of threads per inch is 80, which is much higher than normal weaving. This is also reason why this fabric is only available in 23 inch sizes. After the fabric is woven, it is washed with cold water and beaten with wooden hammers while still moist. Then a paste of wheat flour called glazing is applied on the folds of the fabric. Initially this fabric was made with pure silk, but today it has been replaced by art silk, rayon and staple cotton.

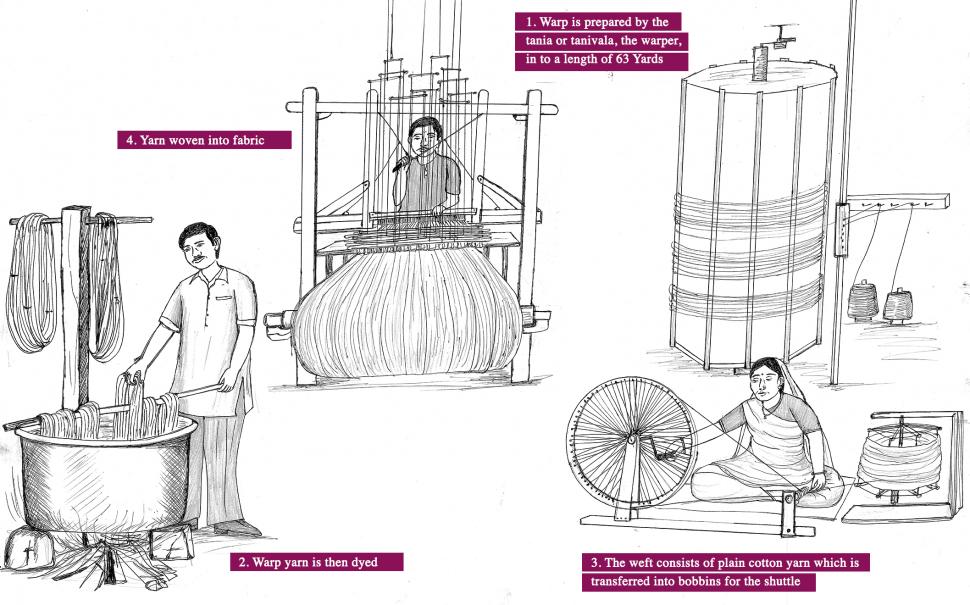

Kutch Weaving

The traditional Kutch weaving is a 600-year-old tradition. It is done by an extra-weft weaving technique, where a weft yarn is used in the warp of the loom. The weaving with extra weft creates the distinctive designs with geometric patterns. The characteristic, intricately handwoven motifs form the identity of the Kutch weaving.

Traditionally Kachchh weaving was carried out on nomadic Panja loom, on which the entire activity was carried by hand. Shuttle looms, a more advanced technology, were introduced later on. There are two types of shuttle looms available across Kachchh– Pit looms and frame looms. The wrap is being prepared through many days process which includes dyeing. The women played major role in preparation of wrap. Various traditional designs were created directly on looms through sequential movements of peddles. The real beauty of Kachchh weaving is the design made from extra weft.

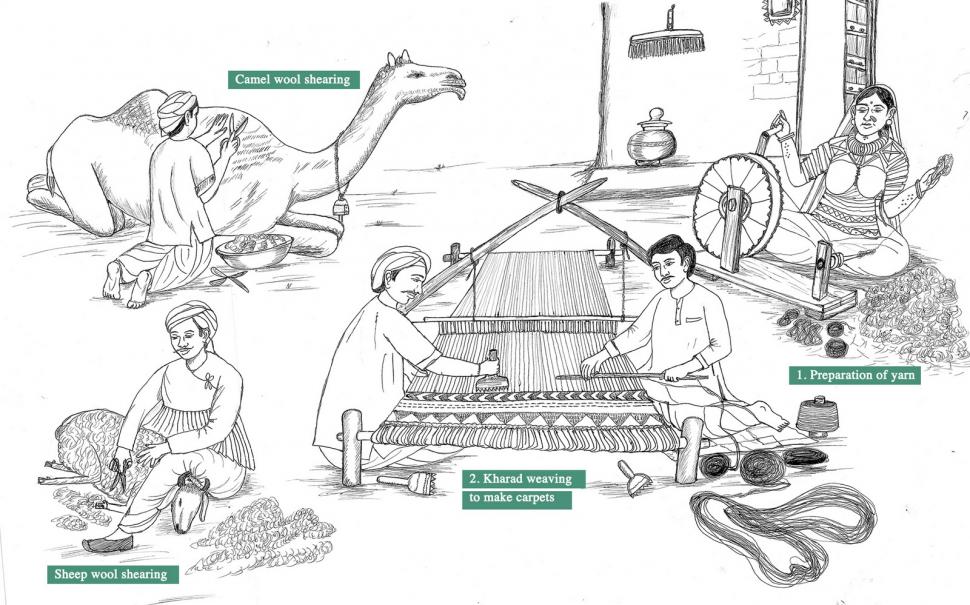

Kharad Weaving

The Community That Has Been Weaving a Legacy

Woven on a nomadic loom, purely by hands, Kharad weaving was widely practised in the desert region of Kachchh up to the end of the last century. These thick rugs, woven by the Meghwal and Sodha Rajput weavers (who practised this craft), were used by the desert communities as floor covers in winters. They even made big shoulder bags, which were used by the nomadic communities to carry their household utilities when migrating. The craft was widely practiced throughout the Greater Rann of Kachchh, but due to a declining local market and lack of raw materials, it now faces a serious risk of dying out. At present, just 4 artisans are the last surviving custodians of this craft.

The Technique

For generations, Kharad rugs were woven from camel, goat, and sheep wool on traditional nomadic looms which could easily be set up and moved throughout the desert. Dyed using both, natural and chemical dyes, these rugs often feature desert-inspired geometric patterns and motifs.

Copper-coated Bell Making

Making a Difference With Bells

The unique melodic tones that emanate from Kachchh metal bells give voice to a centuries-old craft tradition that the Lohar community brought to Kachchh from Sindh, Pakistan. These metal bells, burnished in copper and brass, have long adorned the necks of the cattle, camels, sheep and goats that graze in Kachchh arid plains. The bells signify each animal’s status and position in the herd. Today, the use of Kachchh traditional bells has expanded; they hang in entrance ways, are combined with metal frames to create wind chimes, are finely tuned to become musical instruments, and are used as other forms of festive decoration.

The Technique

Ghantadi or the craft of making metal bells, requires highly refined skills and combined family input. First, men shape each bell, hammering rectangular strips of recycled metal into hollow cylinders. Then, they weld a dome-like metal crown onto the bell’s cylindrical body. Next, artisans bend and attach a metal strip to the crown, so the bell can be hung. Once the bell is shaped, women dip it in a solution of earth and water, covering the wet bells with a mixture of powdered brass and copper. The bell, with its powdered coat, is then wrapped in a pancake of local clay and cotton, and placed in a kiln to bake. After it is properly baked, the clay/cotton mixture is peeled away and any excess clay is rubbed off. Each bell is buffed and polished to accentuate its unique metallic luster, tinted with shades of yellow, gold, red and brown. A ringer, made of a dense wood called sheesham, is attached inside the bell, converting the hollow metal object into a musical work of art.

Leathercraft

The Craft and Community

Leathercraft is one of the non–textile crafts practiced in Kachchh since generations by the Marwada Meghwal community who migrated from Sindh and Rajasthan. Credited for devising ingenious ways to treat the hides of dead animals, often supplied by cattle herders or the Maldhari community, the Marwada Meghwals would then transform them into products that all the communities needed, such as sturdy shoes or products for decorating and adorning of cattle.

Earlier, the tanning and other pre-processes were done at the village level, but gradually disappeared due to cultural and social stigmas. Today, leathers artisans source their leather from leather dealers. The community's women, known for their beautiful embroidery, then decorate the leather goods, combining two craft traditions.

The Technique

Jari Kaam and Torni are few of the many characteristic styles of Kachchh's leather work. In Jari Kaam, silver jari and golden jari are used to create various intricate designs and motifs on the leather items. Traditionally, Jari kaam was practised using real gold and silver to decorate products that were crafted for horses of the royal families. Today, this same work is replicated on objects of modern utility such as shoes, bags and other accessories using artificial threads. On the other hand, Torni is a technique of interlacing, stitching and cutting threads to make pile-like colorful borders on leather goods. The dyeing of leather using locally available dyes is unique to Kachchh.

Lacquer-Turn-Wood

The Community That Adds a Splash of Colour

Been practised as an art form since centuries by the semi-nomadic tribal Wada community, the lacquer obtained from trees and extracted with a stone, is mixed with colours and applied to wooden objects to create kaleidoscopic patterns and make them attractive and colourful. After having moved and worked throughout villages bordering Kachchh's Great Rann, this community then settled in Nirona and Jura where they used the their technical and artisanal skills to sustain the lac-turned-wood craft tradition. They collected natural stones and colours from the forests, made colourful lacquer goods such as furniture and household accessories, and then bartered them with the pastoralist Maldhari community. As of today, there are only a few traditional lacquer artisan families continuing this craft in Kachchh

The Technique:

This craft is practiced using simple handmade tools -- a self-made lathe, a string attached to a bow, and sticks of coloured lac. Each lathe is demarcated by two sharpened iron rods which are bent towards each other at ninety degree angles and fixed in the ground. The distance between them is dependent on the length of wood the artisan is turning because the wood must be held firmly between the rods’ pointed ends. Next, the artisan begins by carving the wood into the desired shape, mixes the lac with colours creating coloured patterns on the object. Traditionally, vegetable dyes were used, but today artisans use brightly coloured chemical dyes. Finally, to help retain the sheen of the objects, groundnut oil is applied.

Upcycled Plastic Weaving

Community Thread

Weaving as a skill has always been intrinsic to Kachchh. Providing employment to plastic waste collectors, area committees, schools, and nearby industries to collect plastic waste, Khamir's Upcycled Plastic initiative is an example of the way craft can alter a space and generate income for economic empowerment. This is a skill that can be easily learnt by neo-weavers and can become a source of supplementary income to medium skilled weavers, home-based workers, disabled and also senior citizens. After the waste plastic is sorted, segregated and cleaned based on its colour and quality, it is then cut into long strips by women from villages near Kukma. These coloured strips are then woven into durable textiles using the pit loom. Nylon is used for the warp, and plastic forms the weft, creating a thick dense material useful for home decor like mats, backpacks, or cushions or accessories.

Ajrakh Hand Block Printing

Tattooing Time on Fabric

A craft which dates back to early medieval times, Ajrakh is said to have been derived from “Azrak”, meaning blue in Arabic, as blue happens to be one of the principal colours in this printing technique. It's also said that the word has been coined from the two Hindi words, “aaj rakh”, meaning, keep it today.

More than a fabric, Ajrakh is considered to be an essential feature of the Sindhi tradition; found in everyday items such as hammocks, bedsheets to dupattas and scarves.

The Technique

Made by the craftspeople from the Khatri community in Kachchh, Gujarat, this block-printing technique borrows heavily from nature: the sun, river, animals, trees and mud are all part of its making. This technique uses mud-resist in the 14-16 different stages of dyeing and printing, which take 14-21 days to complete – a skill that calls for patience and time. This dyeing and printing is repeated twice on the fabric to ensure brilliance of colour; the resulting cloth being soft against the skin and jewel-like in appearance.

Batik Printing

A Craft in Transition

Legend has it that the Batik practice of block printing was being carried out in Kachchh since the time of the Ramayana. Often inspired by the flora, fauna and geometric designs the Khatri community is credited for creating Batik, Ajrakh, Bagru and Bandhani print textiles all over Kachchh. Traditionally, made by dipping a block into hot pilu seed oil, which was then pressed onto fabric. Today, wax is used as a more practical alternative.Since, the adoption of wax has changed the appearance of the textile: thin webs of dye run through the motifs creating a beautiful veiny appearance specified by the designer or the dyer.

The Technique

In Batik printing, paraffin-wax is used as resist material. The wax is first melted in a metal tray with the help of a kerosene stove. Then, a carved wooden block is immersed in the melted wax and printed on a white cloth placed on a table. Prior to this, sand is spread on the table surface, which helps the wax penetrate into the cloth and at the same tIme cool down quickly. The first resist helps retain the white portion of the cloth. Next, the cloth is dipped into a lighter colour, followed by the application of resist once again. This process is repeated a couple of times until the colours penetrate.The wax-resist is removed by immersing the cloth in boiling water, and often reused. Lastly, the cloth is dried and pressed.

Bela Printing

The Last Legacy

Bela prints are bold and graphic. They grab your attention with a vibrant palette of printed color on a plain white background. Diverse hues are achieved using natural and vegetable dyes. Bagru, Rajasthan, is most famous for producing this type of mordant printed textile. Yet, Kachchh has been a producer district of Bela-style cloth for as long as people can remember. Long ago, East Kachchh produced many mordant resist fabrics commonly referred to as Patthar, which were used in dowry gifts.

Red and black colours are iconic of Bela printing, colors which were used the most for their color fastness. Bagru often features large scale and graphic prints, characterized by strong a strong mordant-printing technique wherein the printer applies vegetable dye directly to a piece of cloth with a hand wood block.

Reha Knife-making

Legacies of Collaboration

Six generations of metal knife makers have sustained this Kachchhi craft in Nani Reha and Mota Reha villages. There are two types of knife-making traditions in Kachchh, the chari and the chappu. While the former has a steel or iron blade known as a fur and a handle made from wood, plastic, or brass, the latter is composed of the same parts with an added spring that allows it to fold. Some artisans specialise in crafting the blade, some in casting the handles, and others in polishing the final product. In this system, each knife is the result of many artisans’ collaborative work. A collaborative spirit strengthens the sector and together artisans meet the needs of a consistent demand.

The technique:

Raw materials used for knife making are metals such as brass, iron, copper, zink, aluminium, lead and steel. Majority of the metals are bought from scrap traders based in Bhuj city. For fresh metal sources, the artisans purchase them from traders in Rajkot and Ahmedabad. In the past, artisans used the horns of buffalos to make the handles. They are now replaced with acrylic synthetic material from Anjar. Usually, one artisan carries out the entire production process, this is good for artisanal skills and production efficiency.

Sand Casting

The Community That Recycles Metal Waste

Extensively practiced by the artisans of Reha, sand casting is one of the oldest casting techniques in which recycled metals are melted and poured into one-time used molds made from river sand. Initially involved in metal knife-making, to help sustain this craft, Khamir is working with the artisans to make jewellery products using a similar process in which almost everything is re-used including the sand.

What's In the Technique

First, an epoxy compound model of the designs is created. The caster uses these to make sand molds. Metal rings hold the pressed sand that forms the top and bottom parts of the mold. Then, recycled metals such as household utensils and old pipes are then melted into pourable metal inside a coal-fuelled furnace. This melted metal is then hand poured into stacked molds. After they are cooled, the sand is broken to reveal the objects. Raw unfinished cast pieces fresh out of the sand molds. These are then hand filed and polished to complete the process.

Rogan Art

The Families Painting Hope

While Rogan paintings adorn the walls of the White House, back home, the art is only sustained by two families -- Khatri Abdul Gaffar Doud and Khatri Siddik Hasan. Both have received various awards and won national and international acclaim for the preservation of their art form. Previously, all the members of the Khatri muslim community would practise this art work on various costumes of local animal herders, farming communities, on bridal trousseau and was the exclusive preserve of the male members of the Khatri family. But then over the course, the Khatris started teaching this art form to other crafts people, including women. They successfully managed to revive the dying craft as an art form by making wall pieces for display. The main theme of these wall pieces typically revolve around the “Tree of Life”.

What's in The Technique

Rogan is a form of fabric painting, where the sticky elastic-like paint is made from thick brightly coloured castor seed oil. It is then mixed with vibrant natural colours and immersed in water, before being stored in earthen pots, thereby helping retain its malleable texture. A small place amount of this paint paste is then placed on the palms. Next, the artist uses oversized blunt needles or rods to gently stretch some strands, which are used to draw intricate patterns on the fabric. The artists’ fingers under the fabric help the paint spread and shape the design. As the design are mostly created towards one edge of the fabric, the cloth is then folded to create a mirror image on the other side.

Pottery

Kachchh & Clay

Traditionally, potters shared a very close relationship with different communities in the villages as the communities were totally dependent on the potters to supply the earthenware to not only run the kitchens but also to observe various rituals associated with festivals and related occasions of birth, marriage and death.

The potters work very closely with their surrounding environment. Natural resources such as clay, water, leaves of plant called ‘Jaru’ (local name), thorns and tender stems of ‘Prosopis Julifera’, ‘white clay’ and black stone is required by the potters for activities related to the craft.

What's In the Technique

The Kumbhar community moulds local clay into countless forms of decorative earthenware. They craft a wide variety of vessels such as matka for water storage, ketli to hold tea, and kulada to keep buttermilk. Kumbhar women use red, black, and white clay-based paints to decorate each piece of pottery with distinct community-specific designs. Clay is collected from the banks of local lakes. Artisans transport the clay to their village by tractor or donkey cart. There, they beat the hard lumps of clay into a fine powder. This clay powder is mixed with water and kneaded into an elastic dough. The artisans sit at their potter’s wheel and as the wheel spins, they give shape to the dough, turning it into a vessel.